|

Roger Williams: The Stalwart Idealist

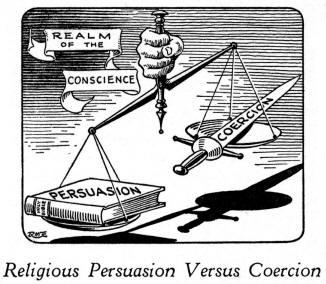

It was fortunate for America that Roger Williams was banished from England by untoward circumstances, and from the Puritan colony by a general court action. Had he not experienced these hardships as a result of a church-and-state union, he might never have seen the clear light of religious liberty in all its fullness nor remained steadfast as its defender to the end of his career. He had tasted the bitter dregs of religious persecution and witnessed the baneful results of a denial of human rights. He saw and experienced all the evil consequence of religious legislation and also of the interference of the civil magistrate in matters of conscience in the prescription and enforcement of religious obligations. He also lived long enough to see his own experiment of a complete separation of church and state develop into the fruition of his brightest hopes. He had the good fortune to found a new government in a wilderness previously unoccupied except by roaming Indians, from whom he purchased the land. There were no cherished traditions or legal precedents from a former administration of government handed down to handicap his new experiment. He had the privilege and unprecedented opportunity to build a republic and create and mold it in harmony with his own ideals. A kind Providence prolonged his days, enabling him to perfect his scheme and to demonstrate that a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, under a complete separation of church and state, produced the happiest results in society that the world has yet witnessed in any human government on earth. He demonstrated that religion prospered best without state aid and without legal sanctions. Williams was so gratified with the beneficent results of his new experiment in liberating the conscience of the individual and in safeguarding that precious heritage in constitutional law which he was handing down to his successors, that he admonished them with these burning words to preserve this priceless legacy: "Having bought the truth dear, we must not sell it cheap; not the least grain of it for the whole world." Roger Williams, as a sound-minded and well seasoned statesman, steadfastly protested to the closing days of his life that "the civil magistrate ought not to punish a breach of the first table of the law, comprised in the first four of the ten commandments." He never receded from his position that the compulsory Sunday-observance laws enacted by the Puritans and the Pilgrims of New England were all wrong and entirely foreign to the gospel plan. The observance of the first four commandments of the decalogue, he held, were duties which man owed exclusively to God, and as such did not fall within the civil duties which man owed to the state. He was confident that God purposely wrote the ten commandments upon two separate tables of stone in order to separate the duties and obligations which were purely religious and spiritual from those which were also secular and civil. He was positively certain that if the civil magistrate recognized this distinction between the religious aspects of the first table of the decalogue and the civil nature of the second table, and refused to enforce the first four commandments, it would lead to the total separation of church and state, and make religious persecution impossible. A kind Providence permitted him to be banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony, where it was impossible for him to work out his experiment, and opened an effectual door for him in Rhode Island to perfect his plans of a truly civil government. Here he realized his ideals and saw "mankind emancipated from the thralldom of priest-craft, from the blindness of bigotry, from the cruelties of intolerance. He saw the nations walking forth in the liberty wherewith Christ had made them free." The learned German historian Gervinus said of Williams that he founded a "new society in Rhode Island upon the principles of entire liberty of conscience, and the uncontrolled power of the majority in secular concerns.... [which principles] have not only maintained themselves here, but have spread over the whole union.... [and] given laws to one quarter of the globe; and, dreaded for their moral influence, they stand in the background of every democratic struggle in Europe." When Roger Williams was accused of sustaining anarchy by his liberal views, and thereby distorting civil government and hindering the progress of Christianity, he wrote his immortal essay on the question, which has been considered an imperishable classic. Among the many wise and good things, he said "There goes many a ship to sea, with many hundred souls on one ship, whose weal and woe is common, and is a true picture of a commonwealth, or a human combination or society. It hath fallen out sometimes that both papists and Protestants, Jews and Turks, may be embarked into one ship; upon which supposal I [do] affirm that all the liberty of conscience that ever I pleaded for, turns upon these two hinges; that none of the papists, Protestants, Jews, or Turks be forced to come to the ship’s prayers or worship; nor [secondly] compelled from their own particular prayers or worship if they practice any. "I further add, that I never denied, that notwithstanding this liberty, the commander of this ship ought to command the ship’s course, yea, and also command that justice, peace, and sobriety be kept and practiced both among the seamen and all the passengers. If any of the seamen refuse to perform their service, or passengers to pay their freight; if any refuse to help, in person or purse, towards the common charges or defense; if any refuse to obey the common laws and orders of the ship concerning their common peace or preservation; if any shall mutiny and rise up against their commanders and officers; if any should [shall] preach or write that there ought to be no commanders or officers because all are equal in Christ, there-, fore, no masters nor officers, no laws nor orders, no corrections nor punishments; I say, I never denied, but in such cases, whatever is pretended, the commander or commanders may judge, resist, compel, and punish such transgressors, according to their deserts and merits. This, if seriously and honestly minded, may, if it so please the Father of lights, let in some light to such as willingly shut not their eyes." Williams took the broad ground from which he never retreated during his whole career, that no man can be held responsible to his fellow man for his religious belief, so long as he respects the equal rights of his fellow men. With equal fervor he maintained that the civil magistrate could deal only with civil things. In his "Bloudy Tenent," in answer to John Cotton, the Puritan, he maintained that the sovereign power of all civil authority is founded in the consent of the people. The ideals and purposes of Roger Williams were wrought out in his experiment in Rhode Island, and he demonstrated to all the world that a government based upon individual initiative and equal opportunity and the free exercise of the conscience in religious matters, was far superior to any government that regimented and prescribed all things to all men. He demonstrated beyond the shadow of a doubt that the happiest, most peaceful and prosperous people are those who live under a government in which the people are ruled by the least legislation necessary. Many believed in religious liberty, but only for themselves. Some believed in the freedom of conscience for others, but the high honor was reserved for Roger Williams to establish the first government upon the consent of the governed, where all men of every religious persuasion and of no religion, and the inalienable rights of the individual, should enjoy the equal protection of the law. Truly did the great American historian, George Bancroft, say of him: "He was the first person in modern Christendom to assert in its plenitude the doctrine of the liberty of conscience-the equality of opinions before the law.... Williams would permit persecution of no opinion, of no religion, leaving heresy unharmed by law, and orthodoxy unprotected by the terrors of penal statutes.... "We praise the man who first analyzed the air, or resolved water into its elements, or drew the lightning from the clouds; even though the discoveries may have been as much the fruits of time as of genius. A moral principle has a much wider and nearer influence on human happiness; nor can any discovery of truth be of more direct benefit to society, than that which establishes a perpetual religious peace, and spreads tranquility through every community and every bosom. "If Copernicus is held in perpetual reverence, because, on his deathbed, he published to the world that the sun is the center of our system; if the name of Kepler is preserved in the annals of human excellence for his sagacity in detecting the laws of the planetary motion; if the genius of Newton has been almost adored for dissecting a ray of light and weighing heavenly bodies as in a balance-let there be for the name of Roger Williams at least some humble place among those who have advanced moral science, and made themselves the benefactors of mankind."-"History of the United States," Vol. I, pp. 282, 283. While the people of Rhode Island did not always adhere strictly to the ideals of Roger Williams after he passed off the stage of action, yet they were exceedingly jealous for the preservation of their peculiar institutions of religious liberty and freedom of conscience which the founder of Rhode Island had bequeathed to them as their peculiar heritage. When the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, in 1787, left the question of the establishment of a state church and of religious liberty untouched and undecided in the Constitution which it submitted to the people for ratification, the people of Rhode Island deliberately refused to ratify the Constitution, and served notice to the Federal Government that they would never ratify it unless and until a Bill of Rights was added that guaranteed absolute separation of church and state, the noninterference of the Federal Government in religious matters, and the unmolested and free exercise of the conscience of the individual in religious concerns. Three years passed by, and still Rhode Island held out against ratification after all the other States had ratified and were operating under the Constitution. Finally Congress threatened the little colony. Bills of coercion were introduced into Congress and discussed. Still Rhode Island said no. The people of Rhode Island repeated their request for constitutional safeguards in favor of religious liberty and the inalienable rights of all men. Steps were taken by the other States to boycott and isolate Rhode Island to compel her to come into the Union by ratifying the Constitution. Even Washington became irked and impatient at Rhode Island’s delay. Hamilton thought she ought to be coerced to ratify. Congress proposed by legislation and by threat of force to bring her into line with the rest of the States. But Rhode Island stood as firm as Roger Williams used to stand in "the rockie strength" of his convictions. She was ready to arm herself, "one man against sixty." At this critical moment James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, who had been ardent disciples of Roger Williams’ principles, came to the rescue. Thomas Jefferson had expressed the wish and hope that some of the States would refuse to ratify the Constitution until proper guaranties of human rights and religious freedom had been annexed. Jefferson said, "By the Constitution you have made, you have protected the government from the people, but what have you done to protect the people from the government?" Madison and Jefferson finally persuaded President Washington to untie the Gordian knot by recommending the annexation of a Bill of Rights to the Constitution. Washington agreed and suggested that Madison become a candidate for the House of Representatives in Congress, so that he could engineer through Congress the adoption of the recommendation for the Bill of Rights. Madison was elected from Virginia upon the pledge that he would secure, if elected, the passage of a resolution to add ten amendments to the Constitution known as "the Bill of Rights," guaranteeing religious liberty as one of the fundamentals of a free people, Because of this guaranty and pledge given to them, the people of Rhode Island ratified the Constitution of the United States on May 29, 1790, and entered the sisterhood of the thirteen original States which completed the union of the United States of America. Yet Rhode Island would not ratify without sending with her certificate of ratification the following request and admonition "That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of ‘discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, and not by force or violence, and therefore, all men have an equal, natural and unalienable right to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience, and that no particular religious sect or society ought to be favoured, or established by law in preference to others." Seventeen days after the ratification of the Constitution by Rhode Island, June 15, 1790, the great Bill of Rights, guaranteeing religious liberty in the First Amendment of the Constitution, together with other inalienable rights, was adopted and placed in the Constitution as the sheet anchor of American liberties. Thus the great principle of religious liberty and the separation of church and state, as well as the ‘principle that civil government should function "in civil things only," which Roger Williams established in the founding of Rhode Island in 1636, became an established principle in the founding of the Federal Government under the Constitution of the United States, as the result of the persistent refusal of the followers of Roger Williams to ratify the Constitution, until assured of religious freedom under the Constitution. Indirectly, Roger Williams became the builder, through the adoption of his ideals, of the greatest republic in the world. If a man’s ideals and work survive him and continue to bring forth a harvest of precious fruit in blessings upon humanity, he is a truly great man. The best way to judge this man is by the contrast between the Puritan scheme of government and the Rhode Island experiment. The Puritans in Massachusetts and Connecticut established their government upon the theory: "Subjection in the Lord ought to be yielded to the magistrates in all lawful things commanded by them for conscience’ sake;" and "matters of faith and worship, . . . or such erroneous opinions or practices, as either in their own nature, or in the manner of publishing and maintaining them, are destructive to the external peace and order which Christ has established in the church, ... may be lawfully called to account, and proceeded against by the censures of the church and by the power of the civil magistrate." The Puritans, in prescribing the duties of the civil magistrate, laid down the following rule: "It is his duty to take order, that unity and peace be preserved in the church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire, that all blasphemies and heresies be suppressed, all corruptions and abuses in worship and discipline be prevented or reformed, and all the ordinances of God duly settled, administered, and observed."-Westminster Confession, 1648, Chap. XXIII, sec. 3. On this hypothesis of government, the Puritans proceeded to unite the church and the state and to enforce every religious obligation, every divine ordinance, and religious custom and observance under the duress of civil magistrate and the penalties of the criminal codes. Everybody was compelled to support the established church by the payment of his tithes, whether he was a member of the church or not. All parents, whether members of the established church or not, had to have their infants officially sprinkled, or suffer punishment at the whipping post or by a fine. Everybody had to attend "divine services on Sunday," whether a professor of religion or not, or pay a fine of ten shillings. All labor and secular business of every kind, except works of necessity and charity, were prohibited on Sunday, under the penalty of the whipping post or fines and imprisonment. One of the Sunday laws read as follows: "Whosoever shall profane the Lord’s day, or any part of it, either by sinful servile work, or by unlawful sport, recreation, or otherwise, whether willfully, or in a careless neglect, shall be duly punished by fine, imprisonment, or corporally. . . But if the court, upon examination, . . . find that the sin was proudly, presumptuously, and with a high hand committed against the known command and authority of the blessed God, such a person therein despising and reproaching the Lord, shall be put to death." Both Massachusetts and Connecticut, under the Puritan regime, enacted more than two hundred fifty separate and distinct compulsory Sunday observance regulations, many of which are still existent upon the statute books of the States which comprised the thirteen original colonies. Roger Williams would have none of these religious regulations upon the civil statute books of Rhode Island. That State never had a compulsory Sunday-observance law upon its statute books, nor any religious obligation enforced under the penal codes, while Roger Williams had a controlling voice in affairs. Nor did he believe the church or any of its schools in which religious education was imparted, should receive financial aid from the general tax fund. He was just as much opposed to subsidizing the religious teacher as he was to paying the clergy from the general tax fund of all the people. His reasons for opposing a state subsidy to religious institutions were sound. It is unjust to tax an unbeliever to support the teaching of religion. State subsidy for the support of religion means state control of religion. To the Puritan clergy this new doctrine was "heresy," and to the Puritan magistrate it was "sedition." When Roger Williams struck a blow at the authority of the civil officers to interfere with church matters and to punish offenses against God and religion, he was condemned and "expelled" by the General Court for "new and dangerous opinions against the authority of the magistrates." He told them that he would "never refuse to obey them in purely civil matters." His persecutors informed him that they were not punishing him "for his religion," but for "sedition," and "disturbance of the public peace," and "jeopardizing the public good." This was the same pretext upon which the pagan rulers of Rome burned the early Christians at the stake. It was this same kind of sophistry that the Jewish ruler invoked when he justified the crucifixion of Christ, saying "that it was expedient that one man should die for the people." Under a religion established by law, irrespective of its kind, whether pagan, Jewish, or Christian, religious persecution is inevitable and religious liberty impossible. As the Jewish hierarchy thought they would put an end to Christ by crucifying Him, so the Puritan hierarchy thought they would put an end to the alleged "dangerous and damnable heresies" taught by Roger Williams by sending him into exile. The Puritans banished him to the wilderness to perish, but Providence watched over him, protected and nurtured him, and gave him the courage of a hero and the spirit of a martyr. God had brought him into the world for such a time and such a mission as this. Persecuted in the Old World from his youth and banished in the New, he was led forth by Providence to a new and goodly land to found an asylum for the oppressed children of God, where the wicked should cease from troubling them. "Careless seems the great Avenger; history’s pages but record One death grapple in the darkness ‘twixt old systems and the Word; Truth forever on the scaffold, wrong forever on the throne Yet that scaffold sways the future, and, behind the dim unknown, Standeth God within the shadow, keeping watch above His own."

|